The iOS graphics series will introduce some content about principle of graphics processing and methods keeping iOS screen fluency, which include screen refresh essential, reason of display stalls, display performance optimising, openGL, AsyncDisplayKit, SwiftUI, etc.

Pixel

The vision of real world is continuous, but it’s not in the virtual digital realm, as the image data is always numerable. For a screen or other display devices, the graphics are only combined by lots of tiny cells that can show RGB colour and are arranged as matrix. People will mistake that the screen are continuous, as long as the cells are enough little. We called these cells as pixel.

Let’s look at the definition: A pixel is the smallest addressable element in an all points addressable display device; so it is the smallest controllable element of a picture represented on the screen. Perhaps the words are boring, so let’s see some practical instances. For the same size images, have more pixels, they’re clearer, since picture could show more details. Like calculous, the image are divided into very tiny parts that approach unlimited little. We use the resolution to measure the number of pixels in an image. We would think this is a mosaic if the resolution of a picture is low, but if it’s very high, we would feel the picture is real.

The regular resolutions are 720p(HD), 1080p(Full HD), 4k.

How Monitors work?

Then, how the pixels are displayed on a screen one by one? This is a long story, we can talk about from CRT monitors.

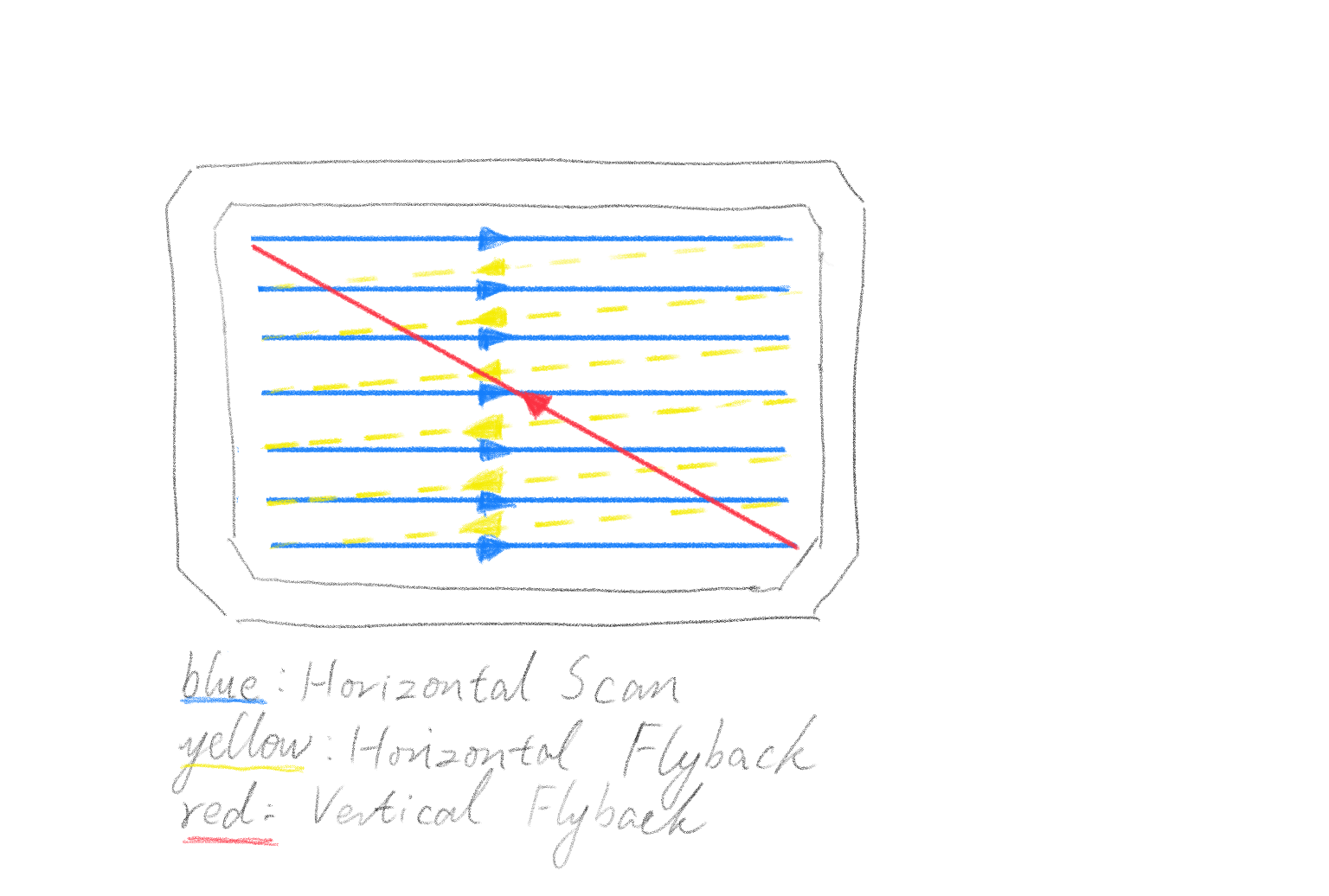

There is an electron gun in a CRT monitors. The gun doesn’t scan it randomly but in a designed fashion. The above figure shows the way. Firstly, it scans from left to right, when the beam reaches the right-hand side of the screen it undergoes a process aka horizontal flyback. While the beam is flying back, it is also pulled a little way down the screen. The gun keeps on repeat this process until the beam reaches the bottom-right side. While this process finishes, a frame of picture is represented on the screen. Then it flies back the initial position for next scan.

The monitors or other display devices use a hardware clock to send a series of timer signals, which is used for synchronisation between display process and video controller. The monitor will send a signal, horizontal synchronisation aka HSync, when the electron gun enter the new row and prepare to scan. After the frame has been drawn and gun has reset, before the next frame ready, the monitor will send a signal called vertical synchronisation aka VSync. In the most cases, the frequency of VSync sent is fixed.

![]()

Nowadays the LED/LCD screens still follow this principle. Like this, all pixels are drawn on the screen and keep on display. If the resolution between image and screen could match, the pixels will be displayed by point to point, which means each image pixel data could map each screen’s colour pixel light. However, if not, a several of colour pixel lights would display in proportion to map one image pixel data.

The frequency of most iOS device such as iPhone and iPad is 59.97Hz, and the iPad Pro can reach even 120Hz.

Why we need GPU?

Although the CPU has helped us do much jobs on programme processing, the GPU perform better, because the GPU is good at computing simultaneously a mass of float digital operations. GPU has hundred, even thousand stream processors, which is an absolutely different design of architecture with the CPUs whose the number of processors is even less, most of them with only 6 or 8. Every stream processor is an independent calculator and just concentrates graphics computing. Graphics processing needs this feature, as it could be regarded as a massive and complex arithmetic test.

So, the CPU and the GPU need to cooperate together during a frame rendering. The CPU prepares and initialises frame data, and then write them into a shared buffer that provide for the GPU to read and shader. About synchronising the CPU and the GPU work in iOS, you can reference Apple’s documentation: synchronizing_cpu_and_gpu_work

The graphics system workflow

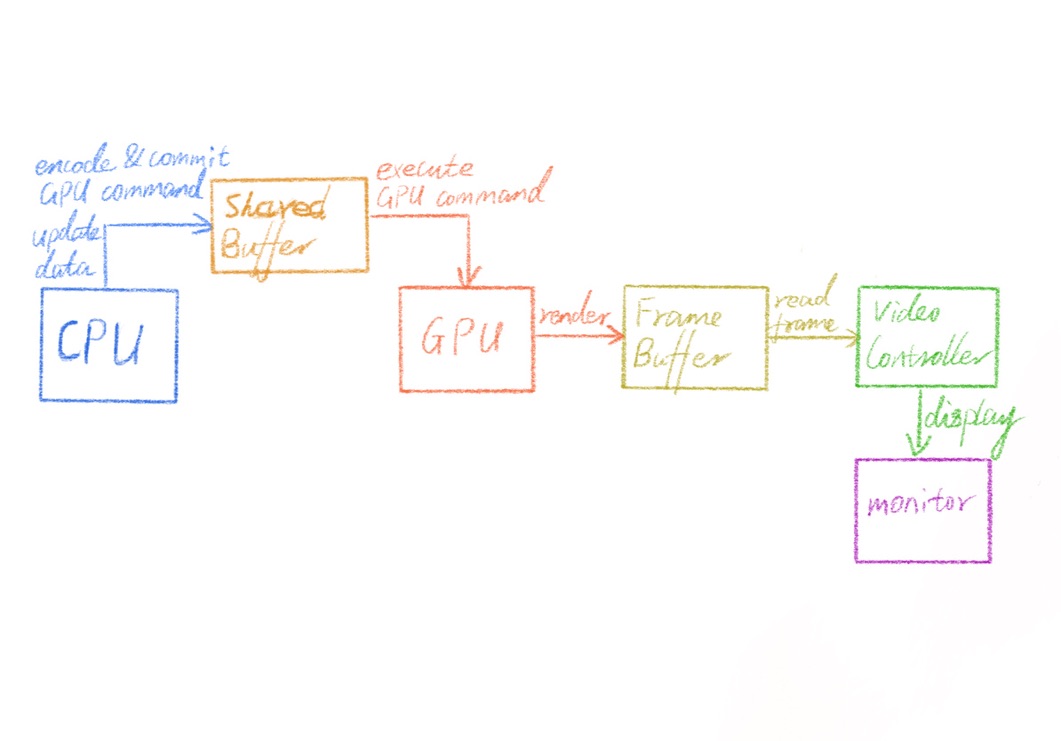

This figure illustrate a workflow of image processing.

The CPU is in charge initialise the instances of image model and update data in a shared buffer. After that, it will encode commands that reference the buffer instance and commit these commands. At this time, the GPU could read data from the shared buffer and execute the commands. These jobs are added in a CPU queue and a GPU queue respectively to conduct in order to protect that frames could be continuously rendered. This is a producer-consumer pattern, the CPUs product data and the GPUs consume it.

Generally, the GPU puts the consequence into a frame buffer after rendering a frame. A video controller read data from this buffer line by line according to VSync, and then the picture is shown on the monitor.

However, this is the simplest model that there is only one frame buffer. The video controller have to wait until that the frame buffer completes being written by GPU. This is a big efficient problem which could lead to stalls, since it is possible that the video controller is still wait for frame buffer, while the monitor has finished scanning. Thus, graphics systems usually set double frame buffer to solve this problem.

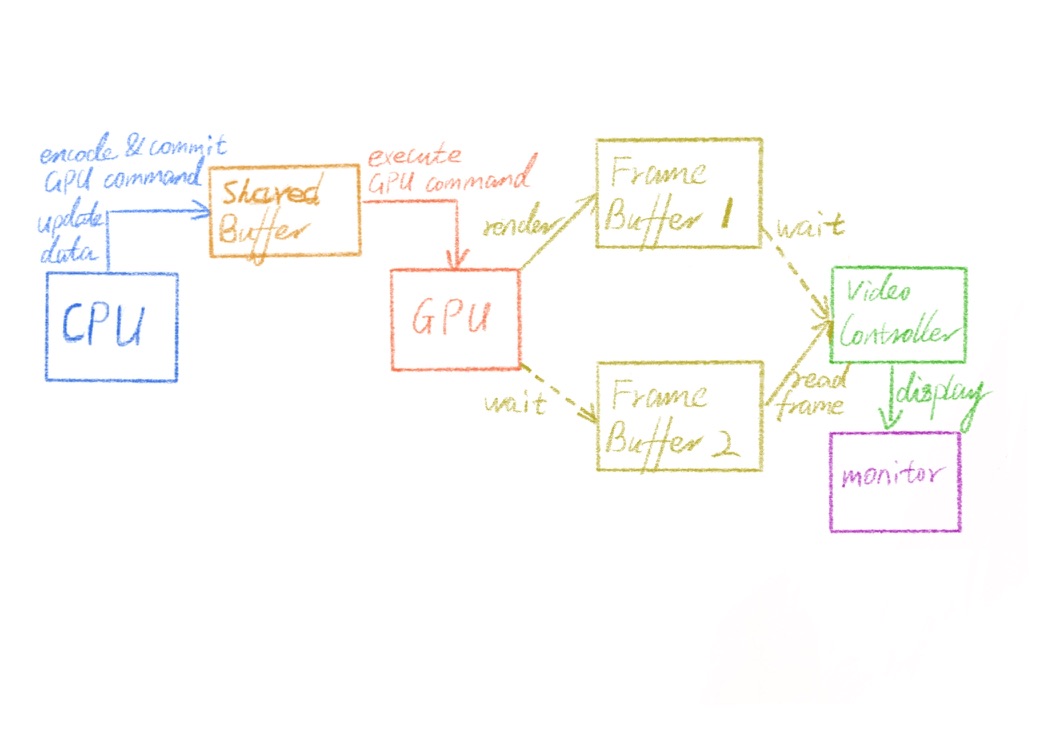

Double frame buffer & its problem

The structure of double frame buffer adopts a swap mode to optimise efficiency. The GPU could pre-render a frame and put it into buffer1, and the video controller would first read it. While the next frame has rendered and written into buffer2, the video controller will indicate buffer2 and read it. Meanwhile, buffer1 will be erased and rewritten by GPU for a new frame. These two buffers keep on swapping states between writing and reading. Like this, the video controller doesn’t need to wait.

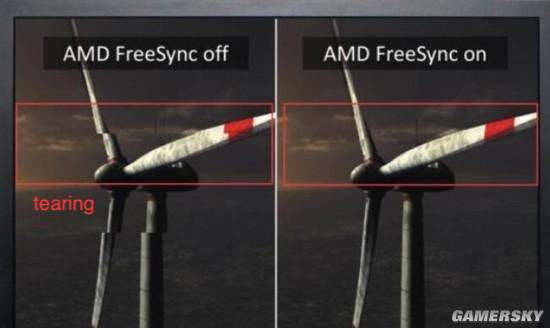

It brings a new problem, although it improves the system. If the video controller hasn’t read, which means the monitor maybe just show a part of frame image, and the GPU has submit the next frame and buffers have swapped, the video controller will draw the rest of new frame on the screen. This always causes picture tearing.

The graphics card firms usually provide a function called V-Sync (AMD call it FreeSync). You must see it on your game or system’s graphics configuration, if you are a game player. This is an effectual method to avoid tearing. The GPU needs to wait until a V-Sync signal from monitor to render a new frame and update the frame buffer. Nevertheless, it wastes much computing resource and the waiting maybe make frames delay.

Reason of display stalls

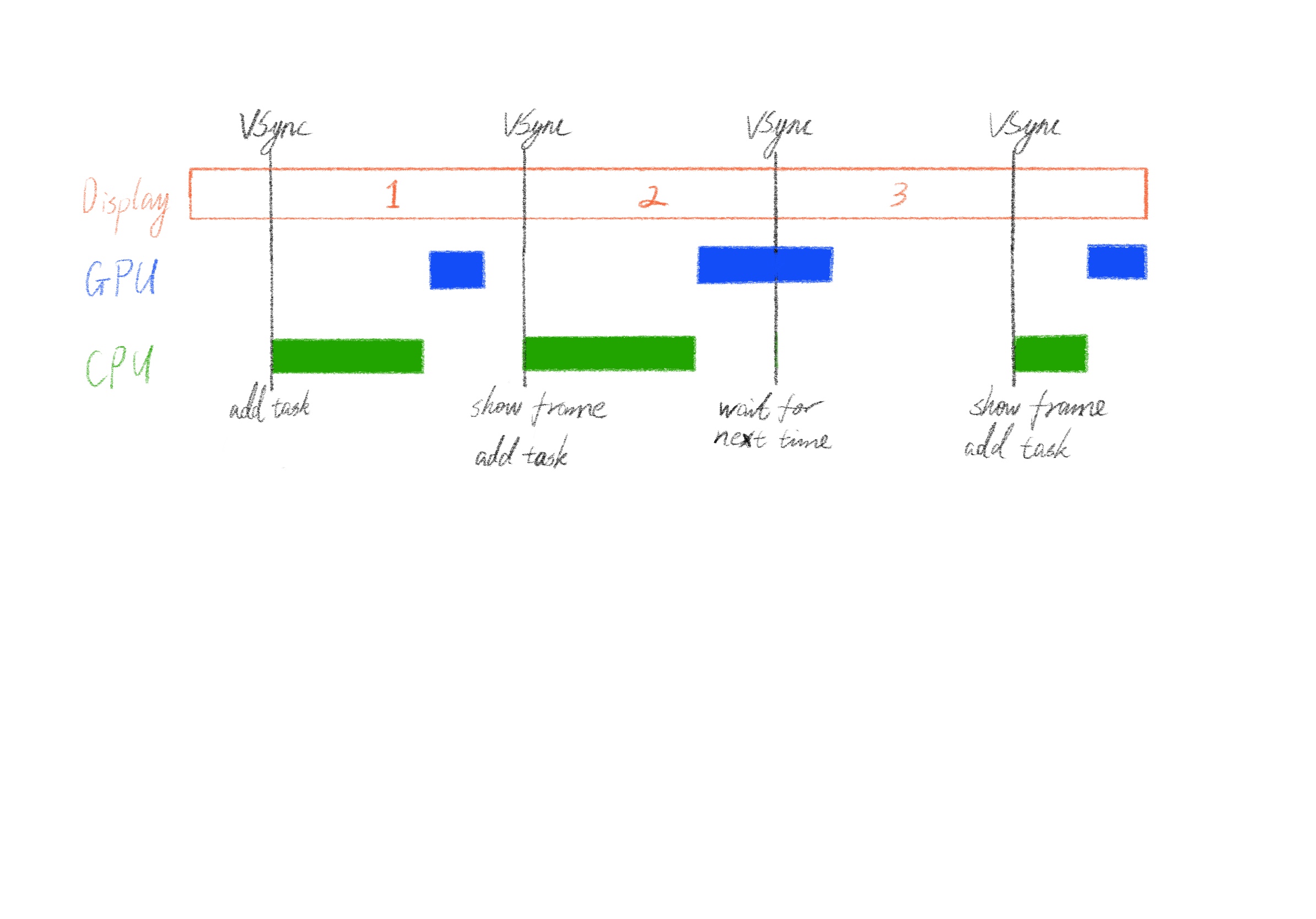

In the iOS, graphic service will notify Application by CADisplayLink after getting VSync signal. At this time, the task such as initialising image data and computing layout will be added in the application’s main thread, and the GPU will execute next task such as converting and rendering in its own thread. The consequence, a new frame, will write eventually into the frame buffer.

The interval of signal dependencies on the refreshing rate. After each interval the video controller will read the current data from frame buffer. If the frame is the newest and complete, it will be shown; if the CPU or the GPU haven’t submit their data yet, processors will go on their jobs, main thread won’t be added a new job until next valid opportunity, and the screen will keep showing the last frame, which is the reason of display stalls.

In short, whatever the CPU or the GPU, both of them spend too much time more than the interval between two VSync, the display will stuck. Thus, the application have to reduce resource consumption of the CPU and the GPU.